In May 1790 the National Assembly urged such a reform, which was to be undertaken by a commission of the Paris Academy of Sciences. The first is the reform of weights and measures. To put the issue in its historical context, two major instances of systematic linguistic change in the revolutionary period will be studied before the medical dimension is discussed in more detail. At the same time it considers political influences on the control of medical practice. This article is, therefore, largely concerned with the influence of language on the unification of the profession. This was soon to be reinforced by the argument of Antoine-François Fourcroy (1755–1809) in 1794 that the physician and surgeon should receive a common training, more practical in nature than physicians had undergone previously. It is not too surprising, therefore, that the French might consider a common term to denote both physician and surgeon. In the new democratic age a title was sought that could be applied equally to all medical practitioners, thus abolishing the traditional superior position of the physician.

French revolutionary calendar change professional#

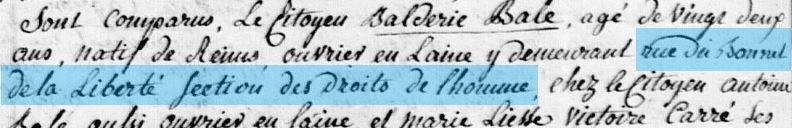

In addition to questions of professional status and education there was the political dimension. 7 By the time of the Revolution, therefore, the status of the more eminent French surgeons was probably rather higher than that of their British counterparts. 6 In many respects the status of the surgeon, or at least of many leading surgeons in towns like Paris, had risen during the course of the century. All these aspects had been parodied by Molière, who created an image of the physician perhaps most justly applied to the ultra-conservative Paris Faculty of Medicine and widely believed by many people in the eighteenth century. On the one hand it was associated with privilege, book learning as opposed to practical skills, and the use of Latin and esoteric terminology. The abandonment of the term médecine had both negative and positive aspects. The most fundamental words relating to the treatment of disease, both as applied to the subject, la médecine, and the practitioner, le médecin, were no longer acceptable. A few revolutionaries went further and described belief in doctors (“ les médecins et leur art”) as a kind of superstition. 4 It was not only religion, however, which was attacked as superstition. Religion, or more specifically Catholicism, could be more easily dismissed when it was described as “fanaticism” ( fanatisme). We shall see that the democratization of language extended to several aspects of medicine. Most famously, the respectful bourgeois titles of Monsieur/Madame were replaced by the universal citoyen/citoyenne. One way of dissociating the new order from the ancien régime was to make certain words and names taboo.

.jpg)

There were many attempts to create a new and better world simply by changing the vocabulary. Language is always important in shaping the social construction of reality and the Revolution illustrates this thesis particularly well.

The distinguished French historian of medicine, Jean-Charles Sournia, has said that the term deserves special attention, but he devotes no more than half a page to it.

2 The adoption of the general term officier de santé (literally “health officer”) to denote all those practising medicine at the time provides a particularly interesting example, which has never been properly studied. 1 One feature which has received some attention is the concomitant change in language. It affected all aspects of society including medicine. The revolutionary period in France was a time of great turmoil.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)